I have finally published this commentary in book form!

Click here to see how you can purchase it from Amazon!

- Chapter 22: Of Religious Worship and the Sabbath Day

- §1 The Regulative Principle Of Worship

- There Is A God

- What Is The Regulative Principle?

- Scriptural Support

- Cain And Abel

- The Second Commandment

- Nadab and Abihu

- You Shall Not Add To It Or Take From It

- Uzzah And The Ark

- Devised From His Own Heart

- In Vain Do They Worship Me

- The Father Seeks Worshipers

- Will Worship And Self-Imposed Worship

- Objection: “But Now We Are In The New Covenant”

- Elements and Circumstances of Worship

- Who Can Worship God Perfectly?

- Not Under Any Visible Representation

- §2 Religious Worship Is To Be Given To God The Father, Son, And Holy Spirit

- Through Christ Alone

- Pray Not To The Dead

- §3 The Doctrine Of Prayer

- What Is Prayer?

- Acceptable Prayer

- Unacceptable Prayer

- Private And Public Prayer

- §4 The Subjects Of Prayer

- §5 The Elements Of The Religious Worship of God

- 1. The Reading Of The Scriptures

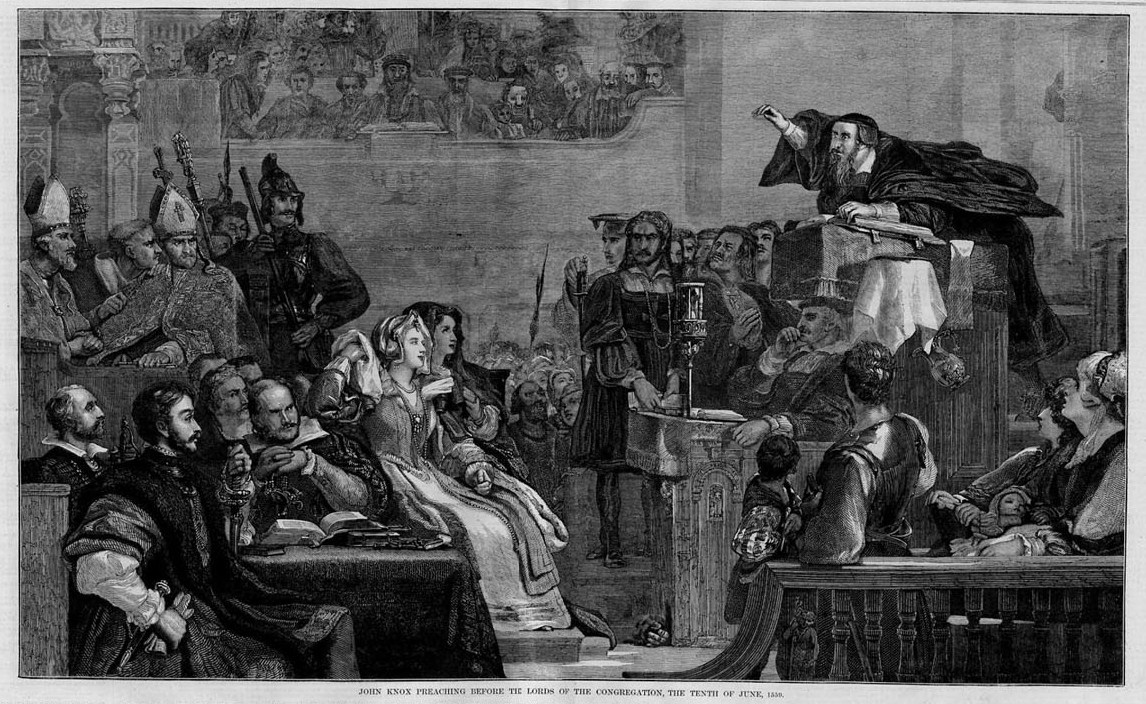

- 2. The Preaching And Hearing Of The Scriptures

- 3. The Singing Of Psalms, Hymns, And Spiritual Songs

- Exclusive Psalmody?

- Musical Instruments?

- 4. Prayer

- 5. Baptism

- 6. The Lord’s Supper

- §6 God Is To Be Worshipped Everywhere In Spirit And In Truth

- §7 The Case For The Christian Sabbath

- Introduction

- My Study

- The Name Of The Day

- Resources

- Written Resources

- Audio Resources

- Video Resources

- The Institution of the Sabbath

- Genesis 2

- Exodus 20:8-11

- Mark 2:27-28

- Conclusion On The Sabbath As Creation Ordinance

- Law Of Nature, Positive Command, Moral, Ceremonial, Temporal

- Law Of Nature

- Positive Command

- Moral Command

- Creation Ordinance

- Unity Of The Decalogue

- Death Penalty And The Sojourner

- The Language Of The Day Being Ceremonial

- Non-Moral Parts

- The Sabbath Before Sinai

- Genesis 4

- Exodus 16

- A Sign Between Me And You

- Under The Old Covenant

- The Seventh-Day Sabbath Pointed To Christ

- Under The New Covenant

- The Lord’s Day, Or The Christian Sabbath

- The Change Of The Day Not Affecting The Essence

- The Christian Sabbath Is Not Contrary To The Fourth Commandment

- The Day Of Resurrection And Appearances

- The Day Of Pentecost (Acts 2:1)

- The Day Of Gathering And Breaking Bread (Acts 20:7)

- The Day Of Contribution (1 Corinthians 16:2)

- The Lord’s Day (Revelation 1:10)

- There Remains A Sabbath-Keeping (Hebrews 3-4)

- They Shall Not Enter My Rest (Hebrews 3:11-19)

- We By Faith Enter God’s Rest (Hebrews 4:1-7)

- The Typology Of The Seventh-Day Sabbath (Hebrews 4:8)

- There Remains A Sabbatismos (Hebrews 4:9)

- The Meaning Of Sabbatismos

- The Already-Not-Yet Tension

- The Change Of The Day (Hebrews 4:10)

- Who is the one who has entered God’s rest?

- The Flow Of The Argument And The Change Of The Day

- Enter That Rest (Hebrews 4:11)

- Conclusion On Hebrews 3-4

- Conclusion On The Change Of The Day

- The Lord’s Day in Early Church History

- Didache (50-120 A.D.)

- Ignatius of Antioch (ca. 35-108 A.D.)

- Pliny the Younger’s Letter on the Christians (112 A.D.)

- Epistle of Barnabas (ca. 80-120 A.D.)

- Gospel of Peter (ca. 150 A.D.)

- Justin Martyr (ca. 147-161)

- Eusebius of Caesarea (pre 325 A.D.)

- Passages Brought Up Against The Christian Sabbath

- Presuppositions

- Romans 14:5-6

- Galatians 4:10

- Colossians 2:16-17

- Conclusion On Supposed Anti-Sabbath Passages

- §8 The Sabbath Is Then Kept Holy Unto The Lord

- Isaiah 58:13-14

- The Place Of Chapter 58

- The Context of Isaiah 58

- Sabbath Observance

- Not Doing Your Own Thing

- Call The Sabbath A Delight

- Blessings For Sabbath Observance

- You Will Take Delight In The LORD

- I Will Make You Ride On The Heights Of The Earth

- I Will Feed You With The Heritage Of Jacob Your Father

- Summary Of Isaiah 58

- Psalm 92

- The Lord Of The Sabbath And The Sabbath

- Works Of Necessity (Matthew 12:1-4)

- Works Of Piety (Matthew 12:5)

- Works Of Mercy (Matthew 12:11-13)

- Summary

- Conscience

- Sabbath-Breakers

- Footnotes

Chapter 22: Of Religious Worship and the Sabbath Day

How are we to worship God? What is the Regulative Principle? Is it taught in the Scriptures? What are the elements of worship? What are circumstances? Are we only to sing the Psalms? Can we use musical instruments in public worship?

Is there a specific day of worship? What is the Sabbath? Which day is it? When was it first instituted? How is it that Sunday is the Christian Sabbath? Where does Scripture teach the change of the day? What about Romans 14:5-6; Galatians 4:9-11; Colossians 2:16-17? Don’t these passages teach the abrogation of the Sabbath? How is the Sabbath to be kept?

§1 The Regulative Principle Of Worship

- The light of nature shews that there is a God, who hath lordship and sovereignty over all; is just, good and doth good unto all; and is therefore to be feared, loved, praised, called upon, trusted in, and served, with all the heart and all the soul, and with all the might. 1 But the acceptable way of worshipping the true God, is instituted by himself, and so limited by his own revealed will, that he may not be worshipped according to the imagination and devices of men, nor the suggestions of Satan, under any visible representations, or any other way not prescribed in the Holy Scriptures. 2

- Jer. 10:7; Mark 12:33[1]

- Gen. 4:1-5; Exod. 20:4-6; Matt. 15:3, 8-9; 2 Kings 16:10-18; Lev. 10:1-3; Deut. 17:3; 4:2; 12:29-32; Josh. 1:7; 23:6-8; Matt. 15:13; Col. 2:20-23; 2 Tim. 3:15-17

The light of nature or natural revelation as we call it shows that there is a God, Who hath lordship and sovereignty over all (Rom. 1:19-23). That there is a God, no one will be able to deny when they stand before God. Both creation and the Creator testify to God. This is basic Romans 1. Furthermore, this God is just, good and doth good unto all (Ps. 145:9) as evidenced by the things which we have and receive. Therefore, He is to be worshiped and served with the whole of our being. Yet He is not to be worshiped as we like. But the acceptable way of worshipping the true God, is instituted by Himself (Ex. 20:4-6; Deut. 4:2; 12:29-32). It is God Who determines how He is to be worshiped. This acceptable way is limited by His revealed will, i.e., Holy Scripture. The unacceptable way of worshipping God as according to the imagination and devices of men (Acts 17:29; Col. 2:23), the suggestions of Satan, visible representations (Ex. 20:4-6) and any other way not prescribed in the Holy Scriptures (Lev. 10:1-3) is abominable to God and He is not pleased with it. God is not to be worshiped as we think He would like to be worship. Why should we think of ways of worshipping Him when He has revealed how He desires to be worshiped? Neither is He to be worshiped through or by any visible representations. This excludes all images and statues of the persons of the Godhead as well as the saints who according to Roman Catholic theology can act as intercessors between us and God/Jesus. The most important aspect of what is called the Regulative Principle of Worship is expressed in the last clause: any other way not prescribed in the Holy Scriptures. Not only is He to be worshiped according to His revealed will, but He is not to be worshiped through that which He has not revealed. If it is not prescribed in the Holy Scriptures, it should not be an element of His worship. If it is prescribed in the Holy Scriptures, it should.

There Is A God

Creation testifies to everyone without question that there is God. General Revelation is sufficient to reveal God to the world and to hold them accountable (see chapter 20). Everyone knows that there is a God. But not only that there is a God, but also that this is a God that must be worshiped. This explains the countless religions that have existed and still exist. It is all because of the Fall that we have a multitude of religions rather than only one. Romans 1 speaks about those who suppress the truth about God through idolatry. All religions in one way or another try to appease the god(s) and serve them. That is the sense that they get from General Revelation. There is a God to Whom they owe their existence and blessings, therefore they are to serve and love Him. But the Confession is quick to add the way in which the true God wants to be worshiped is instituted by Himself alone. To that now we turn our attention.

What Is The Regulative Principle?

In the words of Derek Thomas, “the regulative principle of worship states that the corporate worship of God is to be founded upon specific directions of Scripture.”[2] For everything we do in worship, we must have a scriptural warrant. Sometimes the language of command is used. All that is commanded is acceptable, and what is not commanded is forbidden. We must be careful with such a language. What is meant is not we must have imperatives for everything in corporate worship. But rather, the Regulative Principle of Worship teaches that for every element of worship in the corporate worship of God’s people, there must be a Scriptural warrant. We cannot simply add things to the worship of God which have no warrant in the Word of God.

The Confession says that there is an “acceptable way of worshiping the true God” which presupposes that there is an unacceptable way. We are not to worship God as we feel and as we think He would like us to worship Him. Rather this “acceptable way” is determined and “instituted by himself”. It is God who commands, directs and shows His people in His Word how He desires to be worshiped. How He desires to be worshiped is “limited by his own revealed will”, meaning, the Holy Scriptures. Only things which God (directly) has commanded and/or have a Scriptural warrant may take place in the corporate worship of God’s people. Simply said, the Regulative Principle of Worship is the application of Sola Scriptura to the corporate worship of the Church. This Regulative Principle is contrasted with the Normative Principle. In the time of the Reformation, those who held to the Regulative Principle were the Reformed and the Puritans, while those who held to the Normative Principle were the Lutherans and Anglicans, among others. But, what is the Normative Principle? The twentieth article titled “Of the Authority of the Church” from the Thirty-nine Articles of Religion, reads:

The Church hath power to decree Rites or Ceremonies, and authority in Controversies of Faith: And yet it is not lawful for the Church to ordain anything contrary to God’s Word written, neither may it so expound one place of Scripture, that it be repugnant to another. Wherefore, although the Church be a witness and a keeper of holy Writ, yet, as it ought not to decree any thing against the same, so besides the same ought it not to enforce any thing to be believed for necessity of Salvation.[3]

This is the position of virtually all non-Reformed churches these days. Whatever is not commanded is permitted, unless expressly forbidden. The church may decree “Rites or Ceremonies” but these must not be against “holy Writ”. The Regulative Principle, on the other hand, states that only those things described and commanded in Holy Writ as they concern the worship of God’s people, are to be part of the worship of the Church. Therefore, the Puritans saw a return to Rome in the teaching of the Church of England. They saw that the Normative Principle left the door to Rome open. While the Regulative Principle shut tightly the door to Rome and held fast to Scripture as the basis for the elements and way of worship.

The last observation concerns the fact that this Regulative Principle concerns the worship of the gathered church. The corporate/public worship of the church on the Lord’s Day (or any other day that the church gathers to worship) is to be regulated by the Scriptures alone in all its elements of worship. Not all life is to be regulated by this principle, but only the corporate worship of the church. Therefore, Dr. Waldron speaks of “the regulative principle of the church” and says that “God regulates His worship in a way which differs from the way in which He regulates the rest of life.”[4]After writing about the uniqueness of the church gathering of the New Covenant and its connection with the tabernacle and Temple in the Old Covenant, Dr. Waldron says:

God never told Moses precisely how to construct Moses’ tent. God never told Moses precisely how to regulate His family. Those tasks He left to the discretion of Moses because it was Moses’ tent and Moses’ family. But it is for that very reason that God exercises such pervasive control over the tabernacle and its worship. The tabernacle was God’s tent; it ministers to His family. Thus, He rules its worship with a special and detailed set of regulations to which He expects precise obedience.[5]

God is jealous for His worship and He has actually not given man freedom to do as they will in His worship. We shall shortly see how jealous God is concerning His worship and the way He is worshiped, by the measures He deals to those who pervert His worship. John Calvin is considered to be one of the first who advocated for the Regulative Principle of Worship. In a letter to Emperor Charles V of the Holy Roman Empire (24 February 1500 – 21 September 1558), Calvin writes in 1543:

I know how difficult it is to persuade the world that God disapproves of all modes of worship not expressly sanctioned by His Word. The opposite persuasion which cleaves to them, being seated, as it were, in their very bones and marrow, is, that whatever they do has in itself a sufficient sanction, provided it exhibits some kind of zeal for the honor of God. But since God not only regards as fruitless, but also plainly abominates, whatever we undertake from zeal to His worship, if at variance with His command, what do we gain by a contrary course? The words of God are clear and distinct,

“Obedience is better than sacrifice.” “In vain do they worship me, teaching for doctrines the commandments of men,” (1 Samuel 15:22; Matthew 15:9.)

Every addition to His word, especially in this matter, is a lie. Mere “will worship” ἐθελοθρησκίᾳ [ethelothreskeia] is vanity. This is the decision, and when once the judge has decided, it is no longer time to debate.[6]

Every addition to God’s Word in the matter of His worship is a lie. It is not, Calvin says, a bad suggestion or a bad idea, rather it is a lie. This is a very serious charge. The reason that such a thing is a lie and sin is that it perverts the true worship of God, which should solely be based on what He has said. In conclusion, the Regulative Principle teaches that:

- Whatever is commanded concerning worship is to be done;

- Whatever is forbidden is not to be done;

- Whatever is not spoken about, is not to be done.

Scriptural Support

What is the Scriptural support for this doctrine? We will explore a few examples which will serve to prove that we are not to introduce new things to the worship of God and that it is only the prerogative of God to order and regulate His worship. There are a multitude of examples, but we will content ourselves with a few.

Cain And Abel

Gen. 4:3-5 In the course of time Cain brought to the LORD an offering of the fruit of the ground, 4 and Abel also brought of the firstborn of his flock and of their fat portions. And the LORD had regard for Abel and his offering, 5 but for Cain and his offering he had no regard. So Cain was very angry, and his face fell.

Many have wondered why God was pleased with Abel, but not with Cain. There is no doubt that the offering of sacrifices is part of religious worship. We should also be careful to observe what is said here in the passage. The person and the offering are grouped together. God was pleased and had regard for “Abel and his offering”, but that was not the case for “Cain and his offering”. The problem or the reason for rejection was not only with the person himself but also with the sacrifice itself. Cain brought “an offering of the fruit”, but Abel brought “the firstborn of his flock”. Abel brought a blood offering, while Cain brought non-blood offering. But, you may ask, there is not a single command prior to this event of God commanding a blood offering while forbidding “fruit” offering. So, what was the basis that God rejected “Cain and his offering” then? The reason, I believe, is in what God Himself did for their parents. In Genesis 3:21 we read of the LORD making “garments of skins” for Adam and Eve. The only logical explanation is that God killed some animal(s) to provide their skin as covering for their nakedness and thereby picturing that we need a covering for our sins (Rom. 13:14). Blood was spilled to cover Adam and Eve’s nakedness. God had provided in that event an example of what is pleasing to Him. As G. I. Williamson observes, “Abel gave serious consideration to the revelation that God had given up to that time in history, while Cain treated it lightly.”[7] Dr. Waldron writes:

First, the slaughter of animals to provides [sic] skin coverings for Adam and Eve in Genesis 3:21 is suggestive of the appointment of animal sacrifices. Second, the mention in Genesis 4:4 of “the firstborn of the flock and of their fat” anticipates later appointments of the sacrificial laws. For the sacrificial significance of the firstborn notice Leviticus 27:26 and Numbers 10:37. For the sacrificial significance of the fat notice Exodus 23:18; 29:13; Leviticus 3:3-4, 9-10; 7:3-4, 23-24.

Here we have very early on an example of the Regulative Principle. In fact, we even have it from an example and not a direct command of “You shall.” In the example of the LORD in the Garden, there was sufficient warrant that He only commanded and accepted blood sacrifices. In the blood is the life of the animal (Lev. 17:11), therefore, to offer a blood sacrifice demonstrates that one life had to be given for the other to be spared. We see here, from very early on, the principle of “what is not commanded, is forbidden.” Williamson concludes:

It is no exaggeration at all, then, to say that this was Cain’s downfall: he was not willing to limit himself to worship that had God’s approval.(5) We therefore see a clear principle: worship which is not sanctioned by God is forbidden.[7]

The Second Commandment

Exod. 20:4-6 “You shall not make for yourself a carved image, or any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth. 5 You shall not bow down to them or serve them, for I the LORD your God am a jealous God, visiting the iniquity of the fathers on the children to the third and the fourth generation of those who hate me, 6 but showing steadfast love to thousands of those who love me and keep my commandments.

First of all, we have dealt with this commandment briefly in chapter 19 on the Law of God (see here for that). What does this commandment concern itself with? In the simple, brief or basic form of the commandment, it says, “You shall not make yourself a carved image” or “You shall not have any idols.” The first commandment says “You shall have no other gods.” What is then the difference between the first and the second commandments? I believe the difference lies in this:

- The first commandment teaches us not to have any other god or object of worship other than the LORD God.

- While the second commandment teaches us how we are not to worship this one God.

It is here necessary to dispel the idea that we sometimes may have of the ancients. No one thought that the idol itself (i.e., the image) was the deity they’re worshiping. Rather, the idolaters wanted to get to the deity through that dumb idol. Second, we need to reconsider the idolatry of the golden calf. It is often thought that Israel quickly went astray after other gods in that instance. But in actuality, that is not the case. They had clearly seen the power of God working among them. They were not so dumb as to quickly go after other gods. They knew that there is but one God and He had manifested Himself clearly to them. Well, what was their sin then? Their sin was to worship God through the golden calf! Israel tried to worship God in a way that He explicitly forbad in the Second Commandment, which was declared by God in their hearing. Aaron, who made the golden calf, said, “Tomorrow shall be a feast to the LORD” (Ex. 32:5). That’s the Tetragrammaton! A feast to Yahweh, the true God. As to the “gods” in vv. 1 and 4, the word Elohim is plural even when speaking of the true God, therefore, its translation, among other things, is dependent on the context and the margins mention that it also can be translated “a god” and not “gods.” Support for seeing that it is speaking of a singular god is seen in Aaron’s declaration above. The feast is to be to Yahweh, and not to other false gods. They tried to worship Yahweh in a way which He clearly had forbad in the Second Commandment. They tried to make representations of Him, which He clearly forbad and His wrath was kindled against them. It is generally understood in the Reformed tradition that the Second Commandment has to do with worship. Therefore, the Westminster Larger Catechism says:

Question 109: What are the sins forbidden in the second commandment?

Answer: The sins forbidden in the second commandment are, all devising, counseling, commanding, using, and anywise approving, any religious worship not instituted by God himself; tolerating a false religion; the making any representation of God, of all or of any of the three persons, either inwardly in our mind, or outwardly in any kind of image or likeness of any creature: Whatsoever; all worshiping of it, or God in it or by it; the making of any representation of feigned deities, and all worship of them, or service belonging to them; all superstitious devices, corrupting the worship of God, adding to it, or taking from it, whether invented and taken up of ourselves, or received by tradition from others, though under the title of antiquity, custom, devotion, good intent, or any other pretense: Whatsoever; simony; sacrilege; all neglect, contempt, hindering, and opposing the worship and ordinances which God has appointed.[8]

Nadab and Abihu

Lev. 10:1-3 Now Nadab and Abihu, the sons of Aaron, each took his censer and put fire in it and laid incense on it and offered unauthorized fire before the LORD, which he had not commanded them. 2 And fire came out from before the LORD and consumed them, and they died before the LORD. 3 Then Moses said to Aaron, “This is what the LORD has said: ‘Among those who are near me I will be sanctified, and before all the people I will be glorified.’” And Aaron held his peace.

I think the clearest and most cited example of the Regulative Principle of Worship is the case of Nadab and Abihu. In a sense, you may have sympathy with them and we may see the reaction of God as over the top. But then again, as priests, they had to listen carefully to what God commanded and do that, not turning to the right or to the left. ‘The mere fact that they dared to bring “unauthorized fire” (the translation of the NIV) brought fiery death upon them.’[9]In this case, as was with Cain and Abel, we have the principle of “what is not commanded, is forbidden.”

In Exodus 24:1, Nadab and Abihu are explicitly mentioned and commanded to come and worship in the very presence of God. In fact, the text says “they saw the God of Israel” (Ex. 24:9-10). In Exodus 28:1, they were instituted as priests to the Lord. But in Leviticus 10 we read of the action which brought their immediate death. They dared bring something to the worship of God which He had not commanded. There is not a command that no other fire may be presented before the Lord. The fire which Nadab and Abihu brought was not from the fire which the LORD sent from heaven:

Lev. 9:24 And fire came out from before the LORD and consumed the burnt offering and the pieces of fat on the altar, and when all the people saw it, they shouted and fell on their faces.

This fire lit the burnt offering and the altar. All the other necessary fires had to be taken from this fire. But the fire which Nadab and Abihu brought, was “unauthorized” or “strange” because it came from another source. Then the text explicitly says that concerning this strange fire “he had not commanded them.” John Gill observes:

which he commanded not; yea, forbid, by sending fire from heaven, and ordering coals of fire for the incense to be taken off of the altar of burnt offering; and this, as Aben Ezra observes, they did of their own mind, and not by order. It does not appear that they had any command to offer incense at all at present, this belonged to Aaron, and not to them as yet; but without any instruction and direction they rushed into the holy place with their censers, and offered incense, even both of them, when only one priest was to offer at a time, when it was to be offered, and this they also did with strange fire. This may be an emblem of dissembled love, when a man performs religious duties, prays to God, or praises him without any cordial affection to him, or obeys commands not from love, but selfish views; or of an ignorant, false, and misguided zeal, a zeal not according to knowledge, superstitious and hypocritical; or of false and strange doctrines, such as are not of God, nor agree with the voice of Christ, and are foreign to the Scriptures; or of human ordinances, and the inventions of men, and of everything that man brings of his own, in order to obtain eternal life and salvation.[10]

Williamson observes:

Now it does not say this happened because they were not sincere -- or because they lacked ‘good intentions’; it doesn’t even say it happened because they did something God had expressly forbidden. No, what it says is that they did this without first making sure they had a warrant to do it. So, again we see that worship not commanded by God himself is, therefore, forbidden.[7]

Dr. C. Matthew McMahon likewise observes:

The[y] offered “strange fire”. Now this is somewhat of an odd statement. God never told them that they could not offer this strange fire. You would look through the Scriptures in vain to find the commandment which stated they were not allowed to do this. Rather, we do find what God does tell them. Though God did not expressly forbid this strange fire to be brought, we see from the text that God did not approve of it, and killed them on the spot for offering it.[11]

As I said in the beginning, what they did does not seem to the human mind as a sin deserving of death. It seems that they were sincere and had no evil intentions and they were obviously not expecting to die. But God sees their bringing fire “he had not commanded them” a thing which deserves the death sentence because it perverts His worship, which He is jealous for. By bringing strange and unauthorized fire before the Lord, Nadab and Abihu did not regard the Lord as holy, therefore, He brought immediate judgment upon them, so that the people would know that God is jealous for His worship and He is not pleased with “strange fire.” Again, we have here the principle of “what is not commanded, is forbidden.”

It is proper here to observe how patient God actually is among us. We should not merely think because God does not bring immediate judgment (upon the unregenerate) or discipline (upon His children) for worship which He has not authorized, that God is actually pleased with it. We should not take the patience of God as a sign of His approval of “strange fire…which he did not command them.” Rather, we should all the more and vigorously search the Scriptures to learn about the way in which God wants to be worshiped.

You Shall Not Add To It Or Take From It

Deut. 12:29-32 “When the LORD your God cuts off before you the nations whom you go in to dispossess, and you dispossess them and dwell in their land, 30 take care that you be not ensnared to follow them, after they have been destroyed before you, and that you do not inquire about their gods, saying, ‘How did these nations serve their gods?—that I also may do the same.’ 31 You shall not worship the LORD your God in that way, for every abominable thing that the LORD hates they have done for their gods, for they even burn their sons and their daughters in the fire to their gods. 32 “Everything that I command you, you shall be careful to do. You shall not add to it or take from it.

In warning Israel against idolatry, the Lord likewise commands them to follow His words only. They are to worship the LORD their God in the way that He has commanded them. They should not invent ways of worshiping God as the heathen did for their idols. Rather, the true worship of the true God is instituted by Himself alone. John Gill observes on this passage that we should “neither add any customs and rites of the Heathens to them, nor neglect anything enjoined on them”[10]. The command in v. 32 concerns especially the commandments concerning the worship of God. What is said is also applicable to all of God’s commandments, but especially in this context, to the way which God ought to be worshiped. The people of God should neither add to the worship of God, neither take away from the worship of God. Rather, they are to do everything that God’s commands us concerning His worship. Calvin notes on v. 32:

What thing soever I command. In this brief clause he teaches that no other service of God is lawful, except that of which He has testified His approval in His word, and that obedience is as it were the mother of piety; as if he had said that all modes of devotion are absurd and infected with superstition, which are not directed by this rule. Hence we gather, that in order to the keeping of the First Commandment, a knowledge of the true God is required, derived from His word, and mixed with faith. By forbidding the addition, or diminishing of anything, he plainly condemns as illegitimate whatever men invent of their own imagination; whence it follows that they, who in worshipping God are guided by any rule save that which He Himself has prescribed, make to themselves false gods; and, therefore, horrible vengeance is denounced by Him against those who are guilty of this temerity, through Isaiah,

“Forasmuch as this people draw near me, etc., by the precept of men; therefore, behold I will proceed to do a marvellous work and a wonder: for the wisdom of their wise men shall perish,” etc. (Isa 29:13.)

Now, since all the ceremonies of the Papal worship are a mass of superstitions, no wonder that all her chief rulers and ministers should be blinded with that stupidity wherewith God has threatened them.[12]

Keil & Delitzsch note concerning the place of this command:

Strictly speaking, the warning against inclining to the idolatry of the Canaanites (Deu 12:29-31) forms a transition from the enforcement of the true mode of worshipping Jehovah to the laws relating to tempters to idolatry and worshippers of idols (ch. 13).[13]

Therefore, until the previous chapter, God, through Moses, taught His people the right way of worshiping Him and now He moves to the discussion of idolatry and what ought not to be done in chapter 13. Lastly, Matthew Henry comments:

He therefore concludes (v. 32) with the same caution concerning the worship of God which he had before given concerning the word of God (ch. iv. 2): “You shall not add thereto any inventions of your own, under pretence of making the ordinance either more significant or more magnificent, nor diminish from it, under pretence of making it more easy and practicable, or of setting aside that which may be spared; but observe to do all that, and that only, which God has commanded.” We may then hope in our religious worship to obtain the divine acceptance when we observe the divine appointment. God will have his own work done in his own way.[14]

Uzzah And The Ark

The Ark of the Covenant fell into the hands of the Philistines and was later on delivered from their hands and they placed it in the house of Abinadab (1Sam. 7:1). Now as they are trying to bring the Ark back to Jerusalem from the house of Abinadab, a terrible thing happens. They had brought a new cart, with what it seems to be good intentions so that the Ark of God may not be defiled by an old cart. They were happy, singing and praising the Lord with music. But all the sudden, “the oxen stumbled” and without any intervention, this would have caused the Ark to fall into the dirt. With, what seems to be, all good intentions Uzzah puts his hand so that the Ark would not fall to the ground and is struck down by God. What’s the reason that God judged him so harshly?

Greg L. Price notes that there were three things which caused God’s judgment to come severely upon Uzzah:

The violation of God’s Regulative Principle was at least in three areas: (1) Uzza was apparently not a Levite (he was the son of Abinadab from Kirjath Jearim of the tribe of Judah, cf. 2 Sam. 7:1; 1 Chron. 2:50; 1 Chron 13:6-7) and according to Numbers 4:15 God commanded Levites to move the Ark (cf. 1 Chron. 15:2); (2) The Ark of God was not to be carried on a cart as the heathen Philistines had done in 1 Samuel 6:10-11 (Israel was not to follow the ways in which the heathens served their gods, Deut. 12:30-32). God had specifically commanded the Ark to be carried on the shoulders with poles (Ex. 25:12-15); and (3) The Ark of God was touched by Uzza, whereas God had commanded that no one touch it (Num. 4:15).[15]

Uzzah, along with David, violated the commandments of God concerning the Ark and the carrying thereof. God explicitly commanded that the Ark should be 1) carried by the Kohathites (Num. 3:30-31; 4:15; 7:9); 2) that it was to be carried by poles (Ex. 25:14; Num. 7:9), not upon a cart; and 3) the Ark was not to be touched (Num. 4:15). But Uzzah, David and the priests who should have known better, violated the commands of God. God did not strike them all but only punished Uzzah to demonstrate His holiness as He did with Nadab and Abihu. Right from the beginning, they went wrong in neglecting to inquire what God has actually said concerning how the Ark should be treated. John Gill notes on v. 3:

And they set the ark of God upon a new cart,.... Which was a great mistake, since it ought not to have been put upon a cart, old or new; it was to be borne upon men’s shoulders, and carried by Levites only, and those of the family of Kohath, to whom no wagons were given, when others had them, for the above reason, Nu 7:9;[10]

Israel, in this instance (again), tried to follow the custom of the heathen. The Philistines had put the Ark on a cart (1Sam. 6:7-8), but God’s people should have listened to God’s Word. Uzzah was judged more harshly than the Philistines because he should have known better. The second time they try to bring the Ark to Jerusalem, they know better. David says to the priests:

1Chron. 15:13 Because you did not carry it the first time, the LORD our God broke out against us, because we did not seek him according to the rule.”

Williamson carefully observes:

Uzzah died because -- as David explained later on -- “we did not inquire of [God] about how to do it in the prescribed way” (I Chron. 15:13). It happened, in other words, because they failed to limit themselves to what God had expressly commanded.(12) But how different it was when “the Levites carried the ark of God . . . as Moses had commanded in accordance with the word of the Lord” (I Chron. 15:14). Again we see the same principle clearly revealed: the only thing that pleases God is what He has commanded.(13)[7]

Devised From His Own Heart

The last Old Testament example is that of Jeroboam’s idolatry. After the split of the united Kingdom of Israel into the northern and southern kingdoms, Jeroboam, the king of the northern kingdom, was afraid that the people abandon him and side with Judah, the southern kingdom. That was because of the absence of the Temple in the northern kingdom. What he does is foolishly repeat the sin of Israel at Sinai.

1Kgs. 12:28 So the king took counsel and made two calves of gold. And he said to the people, “You have gone up to Jerusalem long enough. Behold your gods, O Israel, who brought you up out of the land of Egypt.”

As we observed above on the Second Commandment, so likewise here we observe concerning the word “gods” which could also be translated as “god” in the singular. John Gill notes, “that these [the two calves] were representations of the true God, who had brought them out of Egypt; and that it might as well be supposed that God would cause his Shechinah to dwell in them as between the cherubim over the ark.”[10] These words sadly echo what Israel said at Sinai (Ex. 32:4). It appears that Israel had still not learned its lesson. Not only did Jeroboam institute this false worship of images, but also, instead of letting the people go to the appointed place of the Lord, which was Jerusalem, he instituted a false priesthood to promote this idolatry (1Kgs. 12:31). Not only did he do that, but he even appointed a feast by his own authority (1Kgs. 12:32)! The text says:

1Kgs. 12:33 He went up to the altar that he had made in Bethel on the fifteenth day in the eighth month, in the month that he had devised from his own heart. And he instituted a feast for the people of Israel and went up to the altar to make offerings.

He had no divine warrant for such idolatrous and blasphemous ways of worshiping God. He had to follow God’s Law and what it said concerning how He is to be worship and not to devise “from his own heart” how God should be worshiped. After this incident and in subsequent history, Jeroboam becomes an example of a sinful and evil king (e.g. 1Kgs. 10:29, 31; 13:2, 6, 11; 16:2, 19-20, 26; 21:22; 22:52; 2Kgs. 3:3; 14:24; 15:9, 18, 24, 28; 17:21-22; 23:15). Notice especially 2 Kings 10:29. In the next chapter (1 Kings 13), God sends a prophet to prophesy about the abolishment of this false worship. It is obvious that God was not pleased with this innovation of worship which had no basis in His Word. Jeroboam, as the text says, “devised” these things “from his own heart” (1Kgs. 12:33), which was wicked and deceitful (Jer. 17:9). Williamson notes:

Jeroboam was always spoken of, after that time, as the one who “caused Israel to sin” (as a corporate body) (I Kings 15:30). We hardly exaggerate, then, when we say that this was a major source of Israel’s ultimate downfall. Worship which had been appointed by God was replaced by a new form of worship. But because this worship was not commanded by God it was therefore rejected.[7]

What God has not commanded, is forbidden. What God has commanded is to be done and that alone is to be done.

In Vain Do They Worship Me

Mark 7:6-8 And he said to them, “Well did Isaiah prophesy of you hypocrites, as it is written, “‘This people honors me with their lips, but their heart is far from me; 7 in vain do they worship me, teaching as doctrines the commandments of men.’ 8 You leave the commandment of God and hold to the tradition of men.”

Now we come to the New Testament and there is not a hint that the Regulative Principle, so clearly articulated in the Old Testament, has been changed or that we now operate under a different principle. Obviously, some things have been changed such as sacrifices, the Temple, the priesthood and so on. But concerning those, we have a warrant to understand they’re done away with and fulfilled. But there is not a hint in the New Testament that God no longer regulates His worship or that God is no longer jealous for His worship.

The Jews in this passage were bringing a tradition of the elders to the same authority as the Scriptures. They required that they wash in a particular way before eating. Therefore, when they saw the disciples of our Lord eating with “defiled hands” they accused them of “not walk[ing] according to the tradition of the elders” (Mark 7:5). Our Lord’s response is cited above. The first accusation is that they’re hypocrites. They merely appear religious and try to be religious on the outside, but on the inside they’re false. They present themselves as devout to the Word of God, but pay more careful attention to the “tradition of men” than the “commandment of God”. They try to invent ways of pleasing and worshiping God. But God’s response to their innovations is that they are “vain”. This passage the Lord Jesus cites from Isaiah 29:13 from the LXX, which is slightly different from the Hebrew:

Isa 29:13 LXXE And the Lord has said, This people draw nigh to me with their mouth, and they honour me with their lips, but their heart is far from me: but in vain do they worship me, teaching the commandments and doctrines of men.

Their worship is merely outward and is therefore false. Even if it would have contained the right “parts of worship” it would have been false because it was not from the heart. But that was not the only case with the Pharisees. Their heart was not right, but the content of worship was likewise not right. They had added to the worship and commandments of God as the Lord accuses them of doing. In the way that they elevated their “tradition of the elders”, they made void the Word of God and worshiped God falsely and in vain. Calvin notes:

But in vain do they worship me The words of the prophet run literally thus: their fear toward me has been taught by the precept of men. But Christ has faithfully and accurately given the meaning, that in vain is God worshipped, when the will of men is substituted in the room of doctrine. By these words, all kinds of will-worship, ( ἐθελοθζησκεία,) as Paul calls it, ( Col 2:23,) are plainly condemned. For, as we have said, since God chooses to be worshipped in no other way than according to his own appointment, he cannot endure new modes of worship to be devised. As soon as men allow themselves to wander beyond the limits of the Word of God, the more labor and anxiety they display in worshipping him, the heavier is the condemnation which they draw down upon themselves; for by such inventions religion is dishonored.[12]

Philip Schaff notes on Matthew 15:9 that this “vain worship” is “both groundless (without true principle) and fruitless (without proper results).”[16]Christ still, under the New Testaments, holds tightly to the Regulative Principle of Worship. He elevates the commandments of God above the tradition of men. God is to be worshiped in the way which He Himself has instituted. It is His worship and He alone has the prerogative to dictate and regulate it. The traditions of men ought not to be added to the commandments of God. If they do, then God is vainly and falsely worshiped.

The Father Seeks Worshipers

John 4:19-24 The woman said to him, “Sir, I perceive that you are a prophet. 20 Our fathers worshiped on this mountain, but you say that in Jerusalem is the place where people ought to worship.” 21 Jesus said to her, “Woman, believe me, the hour is coming when neither on this mountain nor in Jerusalem will you worship the Father. 22 You worship what you do not know; we worship what we know, for salvation is from the Jews. 23 But the hour is coming, and is now here, when the true worshipers will worship the Father in spirit and truth, for the Father is seeking such people to worship him. 24 God is spirit, and those who worship him must worship in spirit and truth.”

In His encounter with the Samaritan woman, the Lord Jesus goes into a conversation with her about worship. The Samaritans accepted only the Pentateuch and did not worship God in Jerusalem (as they lived outside of Jerusalem). Basically, they did not hold to the Regulative Principle. God had appointed Jerusalem and the Temple to be the place of His worship on earth. But they did not obey the voice of God in this matter. The Lord Jesus says concerning the Samaritans that they “worship what [they] do not know”. But in contrast, “we worship what we know, for salvation is from the Jews” (John 4:22). The Jews worshiped in the place of God’s appointment. The Lord Jesus declares the worship of the Samaritans as false. But He also declares that the hour is coming when the worship of God would not be tied to a particular place. Calvin notes on v. 21—

Woman, believe me. In the first part of this reply, he briefly sets aside the ceremonial worship which had been appointed under the Law; for when he says that the hour is at hand when there shall be no peculiar and fixed place for worship, he means that what Moses delivered was only for a time, and that the time was now approaching when the partition-wall (Eph 2:14) should be thrown down. In this manner he extends the worship of God far beyond its former narrow limits, that the Samaritans might become partakers of it.[12]

But the hour is here when “the true worshipers”, which means that there are false worshipers, will worship God in “spirit and truth”. What does this phrase mean? The word “spirit” here does not refer to the Holy Spirit, I believe, but rather to our own spirit. Thereby it means that the true worship of God is the worship which is invisible and internal. It is the worship with all the heart, mind, soul of the true God. It does not concern itself with outward ceremonies and representations. It does not concern itself with a place worship, whether Jerusalem or Mount Gerizim (as was the case with the Samaritans), but worships God wherever they are. Calvin says on v. 23—

The worship of God is said to consist in the spirit, because it is nothing else than that inward faith of the heart which produces prayer, and, next, purity of conscience and self-denial, that we may be dedicated to obedience to God as holy sacrifices.[12]

Albert Barnes’ comments are likewise helpful on “in spirit”:

The word “spirit,” here, stands opposed to rites and ceremonies, and to the pomp of external worship. It refers to the “mind,” the “soul,” the “heart.” They shall worship God with a sincere “mind;” with the simple offering of gratitude and prayer; with a desire to glorify him, and without external pomp and splendor. Spiritual worship is that where the heart is offered to God, and where we do not depend on external forms for acceptance.[17]

To worship God “in…truth” means to worship Him according to the truth. The Lord Jesus would, later on, declare that “your [God’s] word is truth” (John 17:17). To worship God in truth, therefore, means to worship Him according to His Word. To worship Him according to what He has commanded in the Holy Scriptures. To worship Him according to His liking. We should not add to the worship of God like the Pharisees did who were accused of worshiping God “in vain” (Mark 7:7, see above), lest we want to receive the same accusation. John Gill notes that to worship God in truth means to worship Him

in opposition to hypocrisy, with true hearts, in the singleness, sincerity, and integrity of their souls; and in distinction from Jewish ceremonies, which were only shadows, and had not the truth and substance of things in them; and according to the word of truth, the Gospel of salvation; and in Christ, who is the truth, the true tabernacle, in, and through whom accent is had to God, prayer is made to him, and every part of religious worship with acceptance[10]

John MacArthur writes on v. 24—

in spirit and truth. The word “spirit” does not refer to the Holy Spirit but to the human spirit. Jesus’ point here is that a person must worship not simply by external conformity to religious rituals and places (outwardly) but inwardly (“in spirit”) with the proper heart attitude. The reference to “truth” here refers to worship of God consistent with the revealed Scripture and centered on the “Word made flesh” who ultimately revealed his Father (14:6).[18]

Jesus says that “the Father is seeking such people to worship him.” The worship of God is the most important thing in the world. It is the most important thing for people to concern themselves with. God goes through lengths to regulate His worship and teach His people how He is to be worshiped. Therefore, it is something that is very important to Him. God is seeking those who will truly worship Him in the way that He has prescribed. God desires worship which is “in spirit and truth.” The prime example of this is the Lord Jesus Christ. We should look to Him and learn concerning our duty toward God from God.

“God is spirit” means that He is invisible, without a body. Therefore, those who worship Him, should likewise not worship him, as the Confession says, “under any visible representations”. But rather, we worship Him invisibly, by our spirit and in truth. We do not abide in the shadows and types of the Old Testament, but now we enjoy the realities of Christ in the New Covenant. God seeks those who desire to worship Him in His prescribed way. He teaches us in His Word the way that we should approach Him and worship Him as His people. Therefore, we should pay careful attention to worship Him “in spirit and truth”, which means that we worship Him according to His Word alone without man-made additions.

Will Worship And Self-Imposed Worship

Col. 2:20-23 If with Christ you died to the elemental spirits of the world, why, as if you were still alive in the world, do you submit to regulations— 21 “Do not handle, Do not taste, Do not touch” 22 ( referring to things that all perish as they are used)—according to human precepts and teachings? 23 These have indeed an appearance of wisdom in promoting self-made religion and asceticism and severity to the body, but they are of no value in stopping the indulgence of the flesh.

Our main focus here is the word translated “self-made religion” in v. 23. But let us first observe what is said previously to that in this chapter. We are freed in Christ from the ceremonial laws of the Old Testament, but not only that, we are also freed from everything that is contrary to His Word. These things concern the doctrines of the false teachers about asceticism. We should not submit to their “regulations” (v. 20), which are contrary to the Word but are “according to human precepts and teachings” (v. 22). We should reject these regulations and precepts because they are useless and godless. They do not have the warrant of Scripture and therefore they are vain. These additions to His word, which Calvin says are “a lie”, appear to have wisdom and appear harmless. But in fact, if God has not authorized them, they are forbidden and they promote “self-made religion” (v. 23). Now we turn our attention to this word.

The Greek word is ἐθελοθρησκεία (ethelothreskeia, G1479), which Thayer’s Greek Definitions defines as “voluntary, arbitrary worship” and “worship which one prescribes and devises for himself”.[19]The word ethelothreskeia is a compound of two words. Θέλω (thelo, G2309), which is the verb meaning “to will” and the noun θρησκεία (threskeia, G2356), which means “religious worship.” Therefore, this word is often referred to as “will worship” by those writing for the Regulative Principle and it is thus translated by the KJV and YLT. The NET says “self-imposed worship”. Calvin, noting on this passage, writes of the word “ἐθελοβρησκεία literally denotes a voluntary service, which men choose for themselves at their own option, without authority from God. Human traditions, therefore, are agreeable to us on this account, that they are in accordance with our understanding, for any one will find in his own brain the first outlines of them.”[12]This “will worship” (KJV), “self-imposed worship” (NET) and “self-imposed religion” (ESV) is “according to human precepts and teachings”, which the Church ought not to follow. By forbidding “self-imposed worship”, the Apostle Paul directs the Church to the God-imposed worship—the Regulative Principle of Worship. God ought to be worshiped in the way that He has prescribed, with no additions nor subtractions. Albert Barnes notes:

In will worship. Voluntary worship; that is, worship beyond what God strictly requires--supererogatory service. Probably many of these things they did not urge as being strictly required, but as conducing greatly to piety. The plea doubtless was, that piety might be promoted by service rendered beyond what was absolutely enjoined, and that thus there would be evinced a spirit of uncommon piety--a readiness not only to obey all that God required, but even to go beyond this, and to render him voluntary service. There is much plausibility in this; and this has been the foundation of the appointment of the fasts and festivals of the church; of penances and self-inflicted tortures; of painful vigils and pilgrimages; of works of supererogation; and of the merits of the “saints.” A large part of the corruptions of religion have arisen from this plausible, but deceitful argument. God knew best what things it was most conducive to piety for his people to observe; and we are most safe when we adhere most closely to what he has appointed, and observe no more days and ordinances than he has directed. There is much apparent piety about these things; but there is much wickedness of heart at the bottom, and there is nothing that more tends to corrupt pure religion.[17]

This self-imposed religion and worship in this instance contain also what is said in Colossians 2:18. God is still displeased with worship that goes beyond what He has said in His Word or subtracts from His Word. Deuteronomy 12:32 still stands fast concerning what God has commanded about His worship:

“Everything that I command you, you shall be careful to do. You shall not add to it or take from it.

Objection: “But Now We Are In The New Covenant”

There are several objections to the Regulative Principle which stem from a misunderstanding. I will not deal with those. My purpose was merely to provide a brief case for this doctrine. For those seeking those common objections and their answers, I refer you to Waldron’s chapter in Going Beyond The Five Points. But I will try to deal with one objection here.

Some suppose that just because we are now under grace and not under law (Rom. 6:14), that God is no longer strict concerning His worship. I beg to differ. We should not presume that the patience of God means that He accepts false worship. God is patient and that especially with His children who love Him, but yet do not completely follow His Word concerning His worship. We should not argue, “Oh look, we are not struck down like Nadab and Abihu or Uzzah, therefore God is pleased with everything we do.” But rather, we should diligently search the Scriptures to learn about how has God taught us to publically worship Him as a congregation on the Lord’s Day. Furthermore, God has in fact demonstrated Old Testament-like punishments in the New Testament. Consider the example of Ananias and Sapphira after one lie (Acts 5:1-11). Just because we lie against God and are not struck down, does not mean that God does not care. It simply means that God is unimaginably patient. Or the example of those who abused the Lord’s Supper in the Corinthian congregation. The Apostle Paul says in 1 Corinthians 11:30, “That is why many of you are weak and ill, and some have died.” God has, in fact, visited His people with Old Testament-ish disciplines and punishments (not for their condemnation, I believe). We have no reason to conclude that God is any less jealous for His worship in the New Testament as He was in the Old Testament. Worship is still about God, therefore, He alone still holds the prerogative to regulate and dictate it.

Elements and Circumstances of Worship

Although Confessional Reformed churches believe in the Regulative Principle of Worship, yet their applications of the principle is not uniform. The order in which things are conducted is different. What is sung may be different. There are those who teach that only the 150 Psalms of the Bible are to be sung in corporate worship. While others (including me), believe that non-inspired songs may likewise be sung. Some believe that no instruments may be used in the worship service, while others (including me) do not forbid the use of instruments. All these groups agree about the Regulative Principle of Worship. Some of these groups would accuse the others of not holding tightly to the Regulative Principle. But nonetheless, both groups profess to hold it, yet their application of the Principle is different. My point is: while many churches hold to the Regulative Principle, yet their application is not uniform and there should be some tolerance and biblical conversations about the reasons. Even the Confession, in chapter 1 paragraph 6 admits this:

…there are some circumstances concerning the worship of God, and government of the church, common to human actions and societies, which are to be ordered by the light of nature and Christian prudence, according to the general rules of the Word, which are always to be observed.

There are certain things which God has left us some freedom in, but these concern the circumstances of worship and not the parts or elements of worship. What time do we worship? How long should the sermon be? How long should the service be? How many songs do we sing? How often should the Lord’s Supper be administered? These are circumstances of worship, not elements or parts. Concerning the elements of worship, Tim Challies writes:

Said simply, the elements of worship are the “what” of worship - the parts that are fixed according to Scripture. Examining the New Testament will show the elements that are permitted and commanded by Scripture. These include reading Scripture, prayer, singing, preaching the Word and celebrating the sacraments of baptism and Lord’s Supper.[20]

We will discuss the elements of worship in paragraph 5 of this chapter. The elements or parts of worship is what worship is. The elements of worship define the corporate worship of Christ’s Church. They are the essence. On the other hand, the circumstances of worship, Challies writes:

The circumstances of worship are the “how” of worship - the conditions that determine the best way to worship God within the structure provided by the elements…The Directory of Worship for the Orthodox Presbyterian Church states, “The Lord Jesus Christ has prescribed no fixed forms for public worship but, in the interest of life and power in worship, has given his church a large measure of liberty in this matter.” While there is little freedom in the elements of worship, there is great freedom within them according to circumstances. However, as with every area of life, this freedom must be exercised cautiously and in a way consistent with Scripture.[20]

The circumstances of worship are those things that we could do without. While on the other hand, the elements or parts of worship are the things that we could not do without. If prayer or preaching is removed from the service, then an element and not a circumstance of worship is removed. But if, for example, the service starts at 12 o’clock instead of 10 o’clock, or a church decides to no longer use the beamer, then there is no change in the elements of worship, but merely the circumstances. Derek Thomas observes:

Thus, the regulative principle as such may not be invoked to determine whether contemporary or traditional songs are employed, whether three verses or three chapters of Scripture are read, whether one long prayer or several short prayers are made, or whether a single cup or individual cups with real wine or grape juice are utilized at the Lord’s Supper. To all of these issues, the principle “all things should be done decently and in order” (1 Cor. 14:40) must be applied.[2]

It is in the circumstances where the most differences are found in those churches which hold to the Regulative Principle of Worship.

Who Can Worship God Perfectly?

Christ the Lord was the only Man who has worshiped God perfectly “in spirit and truth.” We all fall miserably short. God demands perfect worship, but we are unable to give God His due. Like all His Ten Commandments, no one can keep them perfectly, because they do not merely concern outward things, but they deal with the heart. Therefore, the Regulative Principle should drive us to the Lord Jesus and we should beseech Him to teach us through His Word and Spirit about how we ought to worship the Triune God “in spirit and truth.” We should pray that we may be further sanctified to worship God more truthfully. Even those who hold to the Regulative Principle are able to sin in not worshipping God truly with their heart. The elements and parts of worship may all be present, but if the heart is not present, it is vain worship.

We should pray that God may grant the grace for a reformation of worship according to His Word. Many churches nowadays do not care about what God has said concerning how He is to be worshiped, but rather look to the world for suggestions. They seek to learn from the world concerning what they desire to see in Church, rather than in the infallible and sufficient Word of God. They seek to draw people using means that God has not authorized and adding to His worship things which He has not commanded. May we pray that God would grant His people the grace and willingness to diligently search the Scriptures to learn about the way in which God desires to be worshiped.

Not Under Any Visible Representation

To worship God by visibly representing Him in statutes or pictures (any of the Person of the Blessed Trinity) is to break the Second Commandment. To worship God “in spirit and truth” includes the idea of worshipping God invisibly, without any representations whatsoever. This does not mean that we may not have pictures of Bible verses or crosses, but it means, that no Person of the Holy Trinity may be visibly represented at all. For more on this see our discussion in chapter 19 about the Second Commandment.

§2 Religious Worship Is To Be Given To God The Father, Son, And Holy Spirit

- Religious worship is to be given to God the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, and to him alone; 1 not to angels, saints, or any other creatures; 2 and since the fall, not without a mediator, nor in the mediation of any other but Christ alone. 3

- Matt. 4:9-10; John 5:23; 2 Cor. 13:14

- Rom. 1:25; Col. 2:10; Rev. 19:10

- John 14:6; Eph. 2:18; Col. 3:17; 1 Tim. 2:5

All three persons of the Trinity, God the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit should receive religious worship and to God alone. No angels, saints, or any other creature (Rom. 1:25; Rev. 19:10) should receive religious worship. It is for God alone. Furthermore, this religious worship is mediated by Christ alone (Eph. 2:18; 1 Tim. 2:5). We cannot go to God without Christ. Christ is our only access to God in all things.

Through Christ Alone

That worship is to be offered to the Triune God is seen from the fact that God ought to be worshiped and that all three Persons of the Holy Trinity are co-equal and co-eternal (see chapter 2). Therefore, worship is to be offered to the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit. All three Persons should be prayed to and worshiped. While that is true, it is usually true, as with prayer, that we worship the Father through the Son by the power of and in the Holy Spirit (not referring to John 4:24). Since the Fall of man in the Garden man needed a mediator, someone who would stand between him and God. The only mediator between man and God, is the man Christ Jesus (1 Tim. 2:5). The Lord Jesus Christ is the only way to the Father (John 14:6). He is the only One in Whom salvation is found (Acts 4:12). It is only through His mediation that we can approach God. Every religion which denies the perfect and sole mediation of the Son, is a false religion. See chapter 8 “of Christ the Mediator.” Many false religions have tried to put either persons alongside Christ, or persons in place of Christ as mediators. Now, to such a religion we turn our attention against which the Reformers wrote.

Pray Not To The Dead

The Roman Catholic religion teaches that not only prayers to God are to be made, but prayers to the departed saints may also be made. Now, simply applying the Regulative Principle of Worship or even looking through the Bible for any example or command to pray for or to departed brothers and sisters, we would search in vain! Scripture is twisted left and right to make it say things which it simply does not say. They often abuse Revelation 5:8 to teach that the saints know the contents of our prayer and therefore, somehow this gives us a warrant to pray to them. These 24 elders are not the Church, but they are angelic representatives of the Church. This is seen in the fact that they exclude themselves from the song of redemption (contra the Textus Receptus) in Revelation 5:9. Moreover, the fact that they know the content of our prayers, does not in any way give us a warrant to pray either to departed saints or to angels. Furthermore, the Roman Catholic religion has an unbiblical understanding of sainthood. The New Testament teaches that all believers are saints (Rom. 1:7; 1 Cor. 1:2; etc…) and that the saints are not a special class of Christians, contrary to Roman Catholicism.

But Catholics will object that the prayer to the saints or through the saints, is just like asking a Christian on earth to pray for you. This is dead wrong and the objection does not work. First of all, those whom we ask for prayer on earth are still alive. Second, that is a thing that we’re directly commanded to do (e.g. 2 Thess. 1:11; 3:1; Jas. 5:16). But contact with the dead is expressly forbidden in the Word. Not only do we not have a command to pray to departed saints, nor do we have a positive example of anyone doing that, but we have actually a negative example. Saul tries to make contact with the now-departed Samuel through a medium and gets rebuked by Samuel in 1 Samuel 28. We are not to have any contact with the dead. We are forbidden by Scripture to have any contact with the dead (Deut. 18:10-12), nor are we anywhere commanded to pray to or through them.

Most importantly, this doctrine is wicked because it casts doubts upon the perfect mediation of Christ. When Roman Catholics pray to Mary and other saints, asking them to intercede with God on their behalf, they are denying the perfect mediation of the Savior. They are asking the departed saints to pray for them from heaven. No such thing has any warrant in the Bible, but the reason why I find it a vile and blasphemous doctrine is because it diminishes the doctrine of Christ’s mediation. Christ is no longer important and He is no longer the only way to God when such heresies are taught. Catholics pray to Mary, ascribing to her all kinds of titles and positions which the Bible doesn’t give her, thinking that their prayers will be better answered, rather than going to the Father directly through the Son. Contrary to this blasphemous doctrine, the Bible states that we may have confidence in our approach to God:

Heb. 4:16 Let us then with confidence draw near to the throne of grace, that we may receive mercy and find grace to help in time of need.

The only Mediator between man and God, is Christ Jesus. There are no other viable candidates. We go to God through Christ and in His Name alone do we make our prayers (John 14:13-14; 16:23-24). To try to put any other person between man and God is to reject the intercession and mediation of the Lord Jesus Christ, our faithful High Priest who “ever liveth to make intercession for [us]” (Heb 7:25 KJV). We have a perfect Mediator through Whom we can confidently come to God by the power of the Spirit. Why should we seek another? Let’s put away all human traditions and heresies and worship God in spirit and truth, according to His Holy Word alone.

§3 The Doctrine Of Prayer

- Prayer, with thanksgiving, being one part of natural worship, is by God required of all men. 1 But that it may be accepted, it is to be made in the name of the Son, 2 by the help of the Spirit, 3 according to his will; 4 with understanding, reverence, humility, fervency, faith, love, and perseverance; 5 and when with others, in a known tongue. 6

- Ps. 95:1-7; 100:1-5

- John 14:13-14

- Rom. 8:26

- 1 John 5:14

- Ps. 47:7; Eccles. 5:1-2; Heb. 12:28; Gen. 18:27; James 5:16; 1:6-7; Mark 11:24; Matt. 6:12,14-15; Col. 4:2; Eph 6:18

- 1 Cor. 14:13-19, 27-28

Prayer is one part of natural worship, that which does not require special revelation. Natural worship is required of all men based on natural revelation. Religious worship is that worship which is based upon His revealed will. That is why prayer to God is required of all men (Ps. 100:1-4). But this does not mean that is accepted or acceptable since God has revealed the way in which we ought to pray. Although God is gracious and answers even some prayers of unbelievers. The acceptable way of prayer is to pray in the name of the Son (John 14:13-14), i.e., based on His authority and graces. It is by the help of the Spirit (Rom. 8:26), realizing our utter need for His guidance and help. Prayer is to be made knowing that our prayer should be according to the will of God (1John 5:14). Prayer is to be made with understanding, knowing what we are asking for. It is to be made with reverence since it is God to Whom we are praying. It is to be made with humility since we deserve nothing from God. It is to be made with fervency, i.e., with zeal and passion. It is to be made with faith that God will give us that which we ask for if it is according to His will. It is to be made with love to God and to others. It is to be made with perseverance, i.e., not giving up when the prayer is not answered quickly (unless led otherwise to not ask for that specific thing) and in preserving in prayer. Prayer in the presence of others should be in a known tongue so that everyone can understand what is being prayed and thereby “amen” it (1 Cor. 14:13-19, 27-28).

What Is Prayer?

Praying to God is “one part of natural worship”. This means that no special revelation is needed to teach us that we should worship God through prayer. It is natural. We want to thank God when there is goodness in our lives and we seek His help when bad things happen. Dr. Wayne Grudem defines prayer as “personal communication with God.”[21] Keach’s Catechism 109 defines prayer as “Prayer is an offering up of our desires to God, for things agreeable to His will, in the name of Christ, with confession of our sins and thankful acknowledgment of His mercies.”[22] God is described as a God who hears our prayers (e.g. Ps. 65:2) and Who answers our prayers (Ps. 143:1). Prayer is an essential and necessary part of religious worship. In fact, the Apostle Paul teaches us to “pray without ceasing” (1 Thess. 5:17) and to pray “at all times” (Eph. 6:18). The Lord Jesus taught us a model of how we ought to pray (Matt. 6:9-13). J.I. Packer beautifully writes of prayer in these words:

God made us and has redeemed us for fellowship with himself, and that is what prayer is. God speaks to us in and through the contents of the Bible, which the Holy spirit opens up and applies to us and enables us to understand. We then speak to God about himself, and ourselves, and people in his world, shaping what we say as response to what he has said. This unique form of two-way conversation continues as long as life lasts.[23]

But for prayer to be acceptable, certain things have to be followed which we now turn our attention to.

Acceptable Prayer

There are, whether you believe it or not, conditions which God places for answering prayer. The conditions are:

- Prayer must be made in accordance with God’s will (Matt. 6:10; Luke. 22:42; 1John 5:14).

- We pray according to God’s revealed will and submit to His sovereign pleasure, knowing that His promise stands fast (Rom. 8:28) and He knows what is best for us better than we do.

- Prayer must be made in the Name of Christ (John 14:13; 16:24; Heb. 13:15).

- Praying in Christ’s Name is not a magical formula, rather, it is praying on the basis of Christ’s work and authority. We pray, pleading with God not on the basis of our righteousness, but Christ’s. The “name” of a person, to the ancients, represented the character and authority of the person. Grudem observes, ‘Thus, the name of Jesus represents all that he is, his entire character. This means that praying “in Jesus’ name” is not only praying in his authority, but also praying in a way that is consistent with his character, that truly represents him and reflects his manner of life and his own holy will. In this sense, to pray in Jesus’ name comes close to the idea of praying “according to his will” (1 John 5:14–15).’[24]

- Prayer must be made in the Holy Spirit (Eph. 6:18; Jude 1:20).

- Relying on His power and graces to intercede on our behalf (Rom. 8:26-27).

- Prayer must be performed in faith (Jas. 1:6; Matt. 21:22).

- The one making the prayer should keep God’s commandments (1John 3:22).

- Prayer must be made with confession of sin (Jas. 5:16; Ps. 66:8).

- So that we would remove hindrances that may stand between us and God. We, first of all, confess all known and unknown sins and ask for forgiveness and cleansing.

- Prayer must be made with good intentions and motives (Jas. 4:3; 1 Pet. 4:11).

- Prayer must be made with thankfulness (Phil. 4:6; Col. 4:2; 1 Thess. 5:16-18).

- Two things that I can always pray for are confessing my sins and thanking God for His amazing grace. We should always be thankful to God for everything.

- We must pray continually (Luke 18:1; 1 Thess. 5:17; Col. 4:2).

- Prayer must be made with pure hearts (Isa. 1:15-16; Heb. 10:22; Ps. 66:8).

- Prayer must be made with a forgiving spirit (Mark 11:25).

- Prayer must be done with the glory of God as the goal (1 Cor. 10:31).

These are the things which the Bible teaches us about how prayer is to be made and it touches upon all of the things which this paragraph of the Confession touches on except on one point. Prayer, in public form, is to be made in a known language. I should not pray in Armenian or Arabic, in an English or Dutch church. A prayer must be made in a known and understand language so that others may “Amen” it. This follows the principle that Paul laid for tongue-speaking in 1 Corinthians 14:13-19.

Oftentimes, God answers our prayers out of amazing grace, even when we do not follow the prescribed ways of prayer. But this does not mean that it is irrelevant and we should neglect what God has said about acceptable prayer. Rather, it should demonstrate to us the magnificent and mind-stretching grace of God toward us and our sinfulness.

Unacceptable Prayer

Just like the Bible speaks of prayer that is acceptable to God and which God will answer, so likewise, the Bible speaks of prayer which is unacceptable to Him. In many ways, this is simply the negative of what was said concerning the conditions of acceptable prayer, but there are some positive statements in the Bible concerning prayer which does not delight God. The amazing fact is that oftentimes, God does, out of amazing display of grace and patience, answer these “unacceptable” prayers.

- The prayer of unbelievers (Prov. 15:8; Ps. 34:15-17; John 9:31; 1 Pet. 3:12).

- The prayer with the wrong motives and intentions (Jas. 4:3; Prov. 21:27).

- The prayer of the one who loves sin (Ps. 66:18; Isa. 1:15-17; Micah 3:4).

- The prayer of those who do not fear the LORD (Prov. 1:28-30).

- The prayer of those who do not help the poor (Prov. 21:13).

- The prayer of those who have problems with their spouses (1 Pet. 3:7).

- The prayer of those who doubt and are double-minded (Jas. 1:6-8).

- The prayer of those who want to be seen by people (Matt. 6:5; Luke 18:9-14).

- The prayer of those who heap up empty phrases (Matt. 6:7).

Private And Public Prayer

From the statement of the Lord Jesus in Matthew 6:6, some have supposed that public prayer is not to be offered. Otherwise, we would be praying like the Pharisees who wanted to be seen by men. Rather, true prayer is private in one’s room. So they reason. But this is wrong. The Lord Jesus does not forbid public prayer, what He forbids is hypocritical prayer, which is done not to honor and worship God, but rather to be seen as pious by men. That is the context of that passage. Rather than praying to “be seen by others” (Matt. 6:5), the Christian should pray in secret (Matt. 6:6). He hereby does not forbid public prayer, rather contrasts false and true prayer. He contrasts those who pray to be seen by men and those who do not care to be seen by men, who even go to the privacy of their room without anyone knowing that they’re praying. The Lord Jesus Himself goes on to pray loudly and in public in vv. 9-13 and on other occasions (e.g. Matt. 11:25-27; 26:36; John 17). Therefore, the interpretation which excludes public prayer cannot possibly be right.

Public prayer, just like private prayer, is commanded. 1 Timothy 2:8 says:

I desire then that in every place the men should pray, lifting holy hands without anger or quarreling;

The men are to lift their hands and pray. This most likely refers to the gathering of the Church. The early church prayed publicly and loudly together (Acts 4:24ff; 20:36). Furthermore, there is a warrant for public prayer in the Old Testament too (Neh. 9; Ezra 10). When the context of Matthew 6:6 is properly understood, we see that the Lord Jesus says nothing negative about public prayer.

§4 The Subjects Of Prayer

- Prayer is to be made for things lawful, and for all sorts of men living, or that shall live hereafter; 1 but not for the dead, nor for those of whom it may be known that they have sinned the sin unto death. 2

- John 5:14; 1 Tim. 2:1-2; John 17:20

- 2 Sam. 12:21-23; Luke 16:25-26; Rev. 14:13; 1 John 5:16